Photographer Jack Sullivan joined me as my travel companion on the trip to Cuba in March 2023. Jack shoots and writes full time for the Island Institute - a non profit community advocacy organization in Rockland, Maine. Our interest in documenting similar subjects and learning about coastal fishing communities and shared passion for photography made us a great team for this two week adventure.

In the post below with his prose and photographs, Jack recounts the unique experience that we had while traveling to off the beaten path l0cations and immersing ourselves into the communities that we were documenting.

Jack Sullivan photographing the full moon setting at the waterfront in Cojímar, Cuba - a small fishing community just outside of Havana.

What happens when you take two photographers known for their work in rural fishing communities and let them loose on the island of Cuba? Naturally, they’re going to seek out the fishing villages and befriend the folks who make their livelihoods on the water.

When Jay came to me in search of an adventure companion for his March 2023 trip to Cuba, I accepted the invitation without hesitation. I live in rural Maine where I document the lobstering communities along the coast and islands, shooting for a community development nonprofit called the Island Institute. I’ve had the pleasure of shooting with Jay when he comes up to my home state on his photography travels. Every time I shoot with Jay, I take the best photos of my career. He encourages me to pick up on innovative techniques, see new perspectives, and re-think compositions. We share a lot in common—our passion for island fishing communities, love of antiques and birds (especially antique birds), and of course, our dedication to photojournalism. Another similarity that would come in handy on our Cuba adventure is between the two of us, we can nearly speak and understand Spanish.

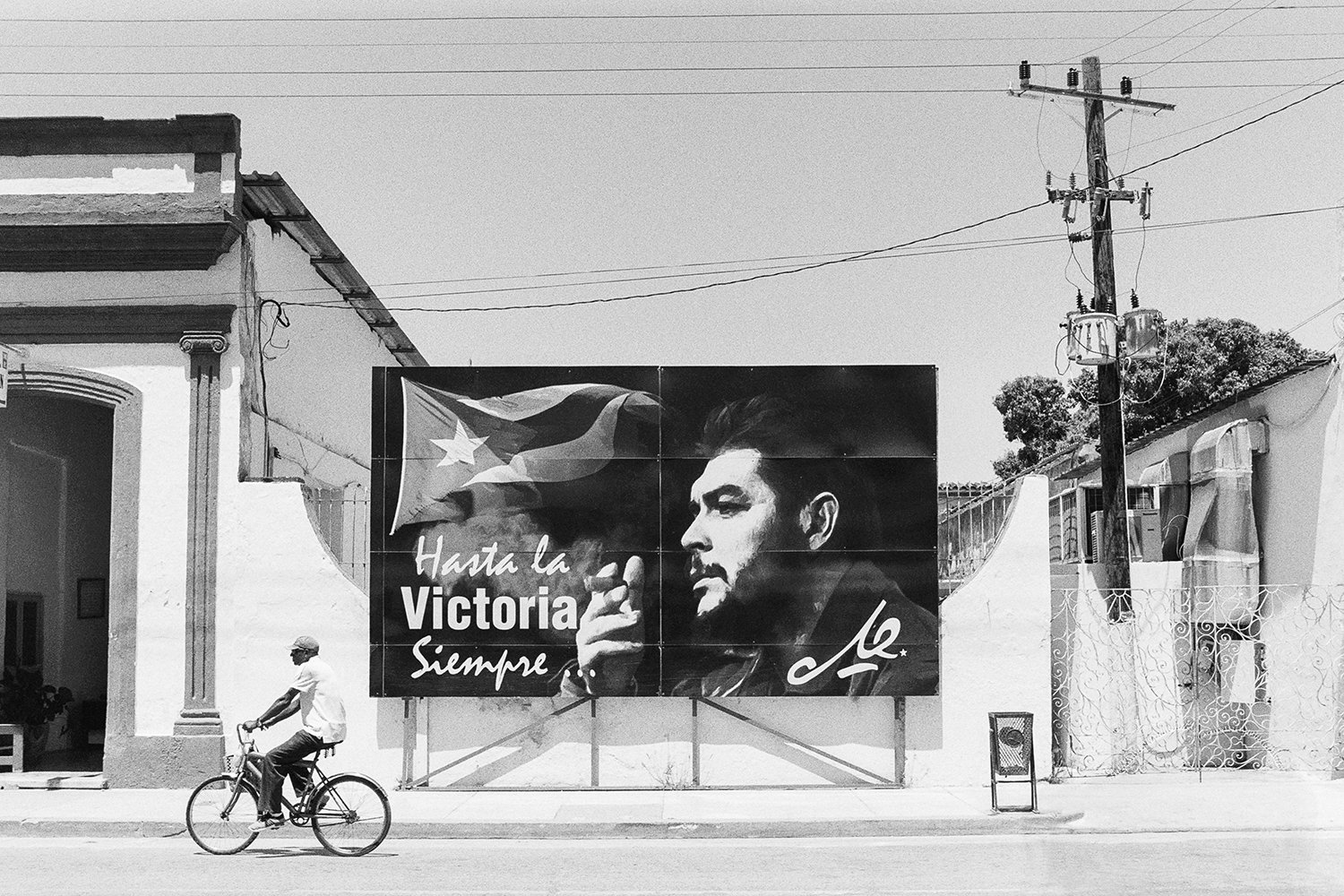

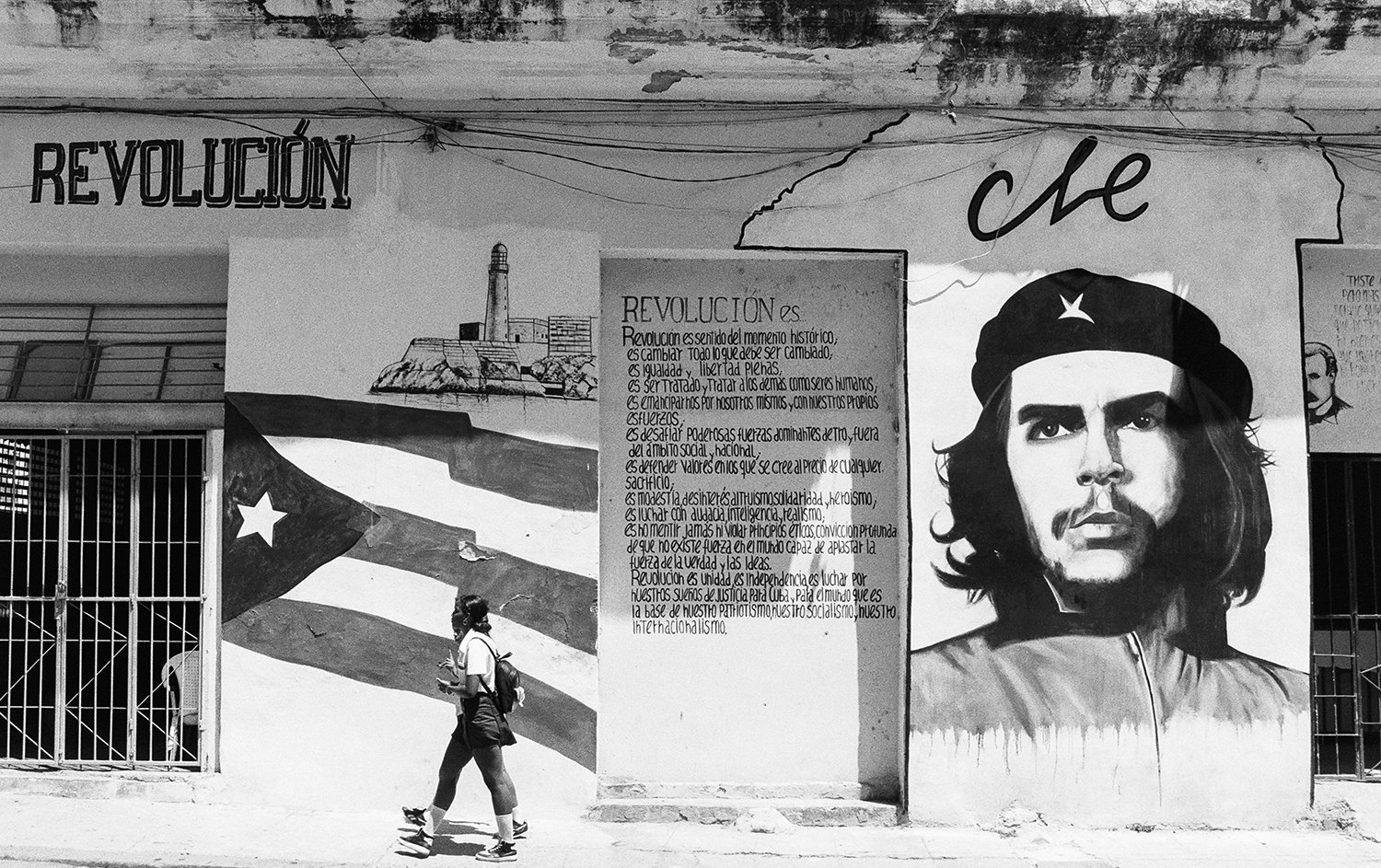

Despite being only 90 miles away from Florida, English is not widely spoken in Cuba. Many parts of our culture do not permeate throughout Cuba, and this is not altogether coincidental. The Communist government of Cuba holds a longstanding negative relationship with the United States government that dates back to Cold War tensions. Trade and tourism are heavily restricted between the U.S. and Cuba, making U.S. goods and citizens rare on the island. This relationship (or lack thereof) between the two countries is largely based off outdated animosities, animosities we certainly did not experience from the folks who let us tell their stories with our cameras.

We spent our time on the northwestern half of the island, landing in and departing from Habana, the capital. We spent time in Cojímar, Caibarién, Isabela de Sagua, and Playa Larga, all villages on the ocean with working waterfronts and fishing fleets. Because of the sensitivities surrounding U.S.-Cuba relations, and general wariness of Cuban authorities, getting access to the boatyards was often a challenge. “No se puede” or “it cannot be done” was often the answer when we asked to enter. Thankfully, our smiles and broken Spanish often gained us entry after we convinced them we meant no trouble and only wanted to share their stories with our friends, families, and audiences at home. Some of the most memorable encounters include Cuni, the oyster fisherman in Isabela de Sagua who has been chipping oysters—or ostiones—off pilings and rocks, shucking them, and hand-delivering them to restaurants for decades. We met Evelyn in Cojímar who generously let us photograph his now famous dory (also named Evelyn) while his friends teased him from across the river. And Rey from Playa Larga proudly presented to us his sailfish for trophy photos. Representing some of the most dedicated and talented anglers in the world, fishermen like Rey can reel in a fifty-plus-pound sailfish from a small rowboat using a handline.

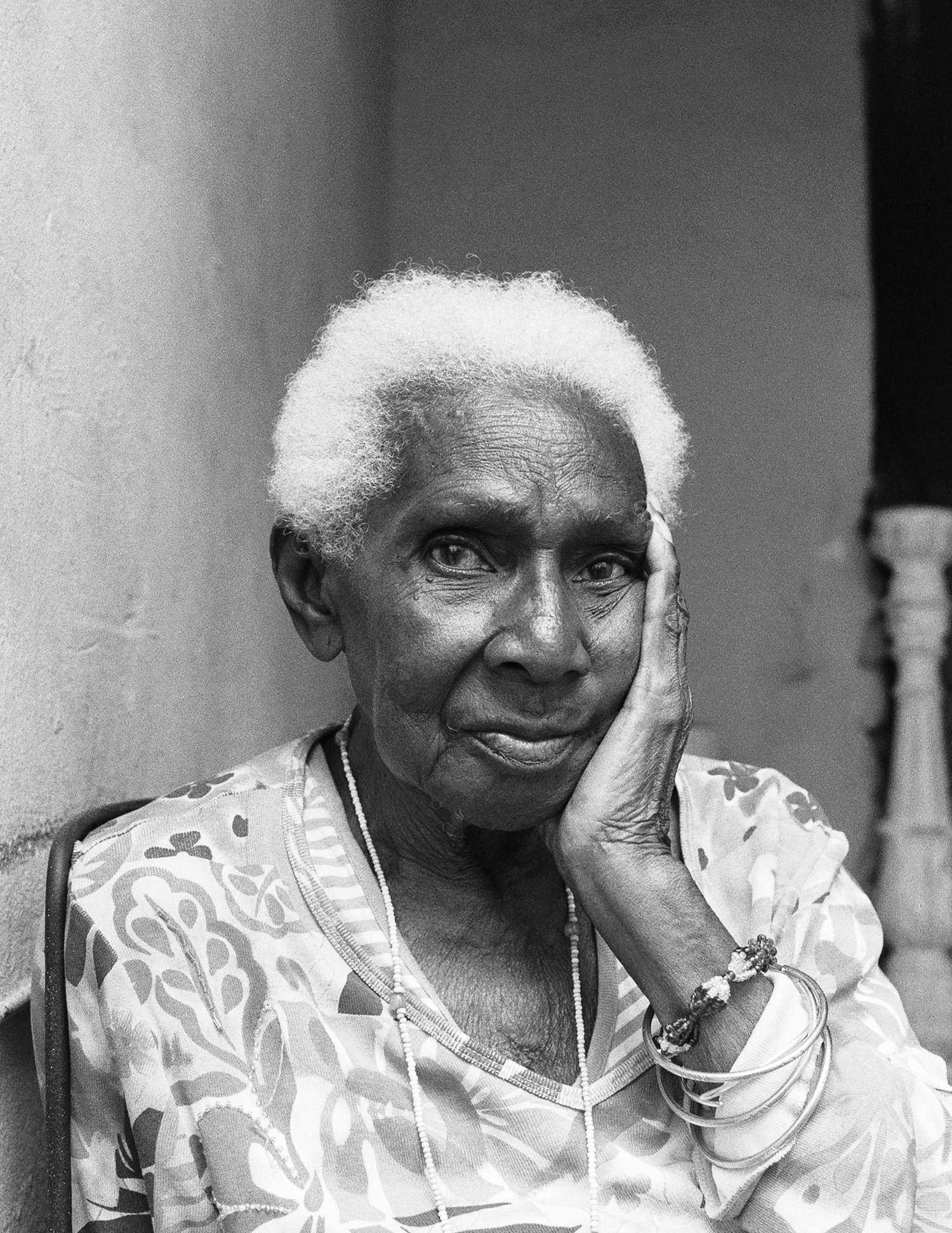

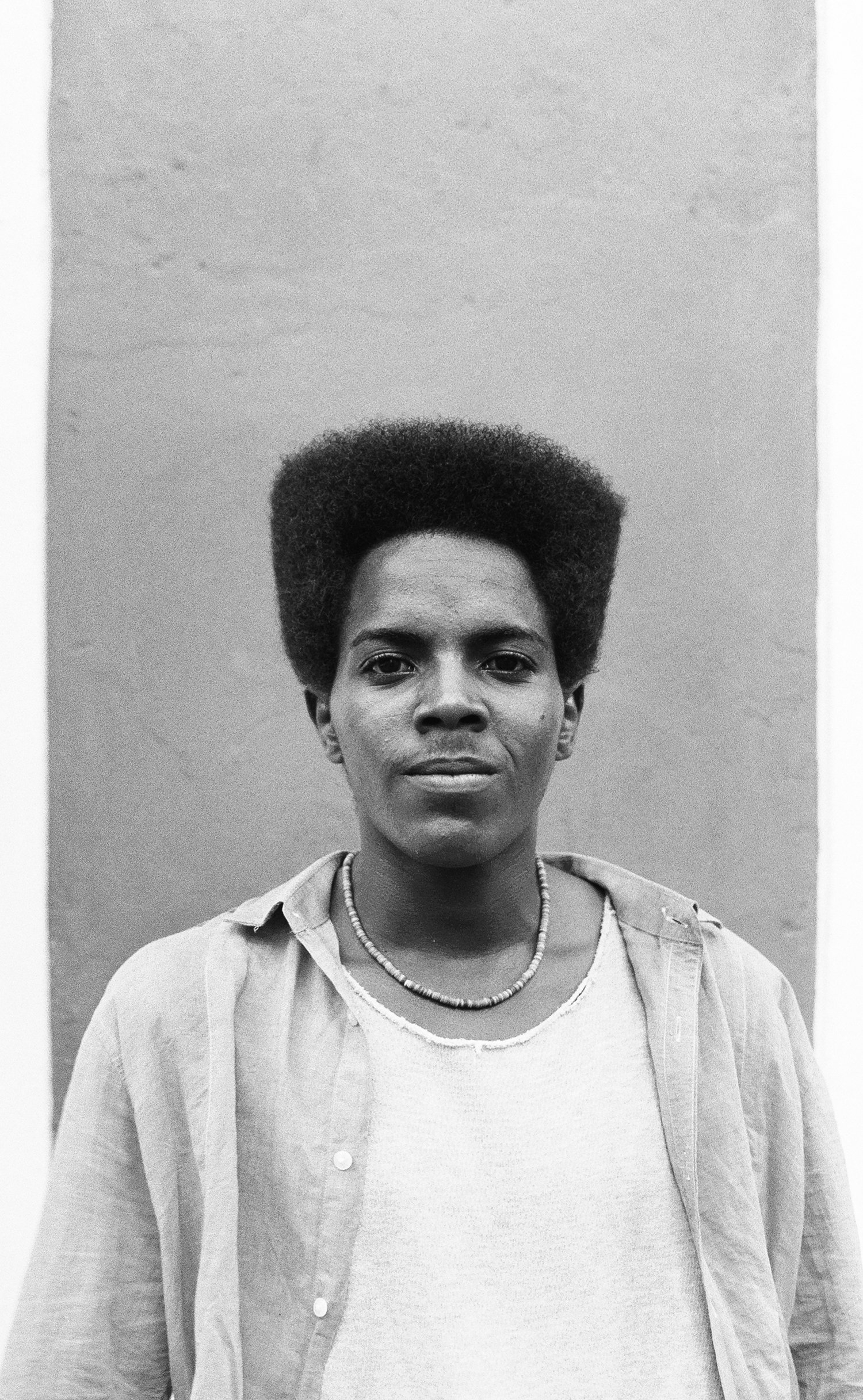

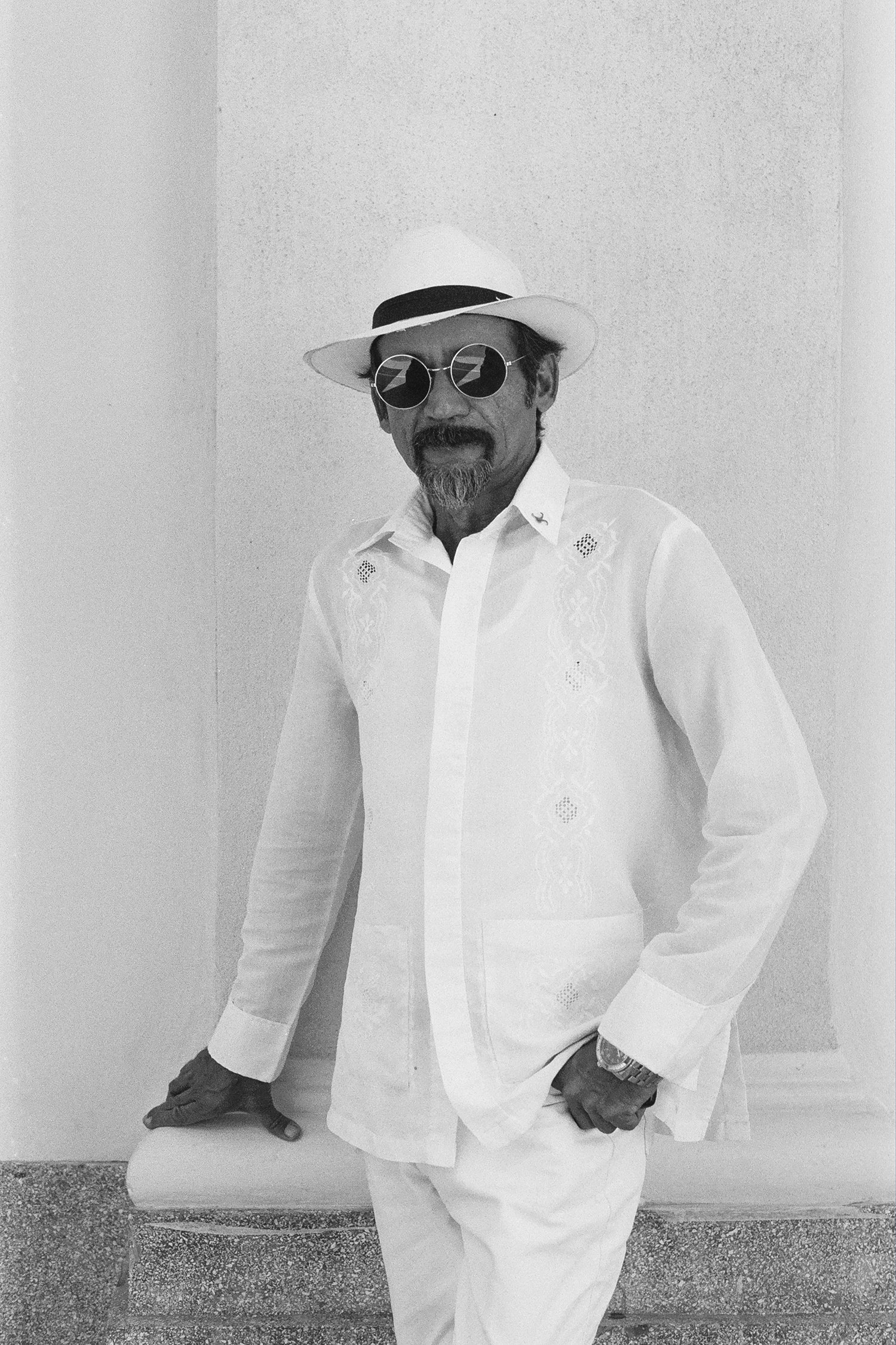

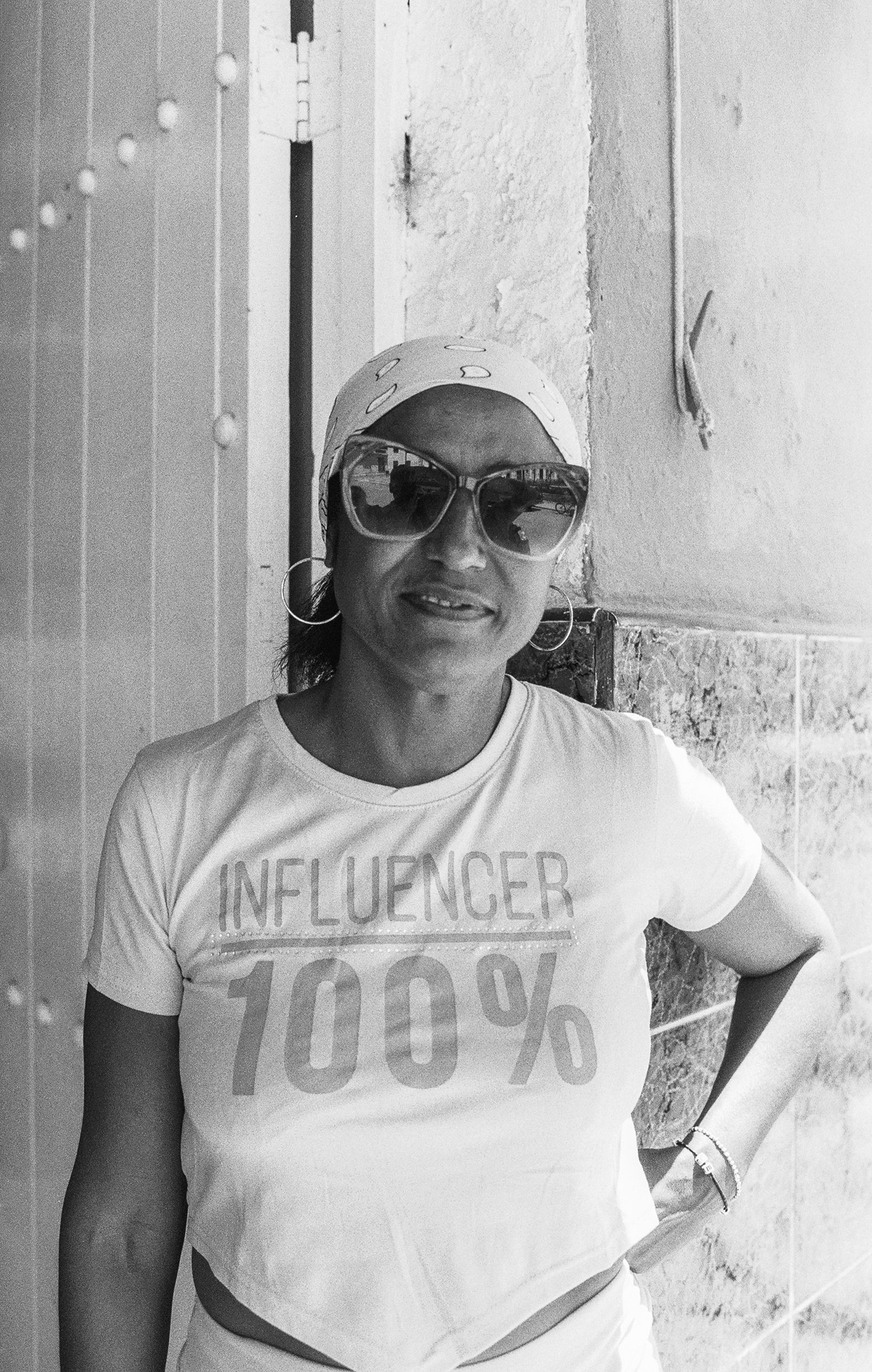

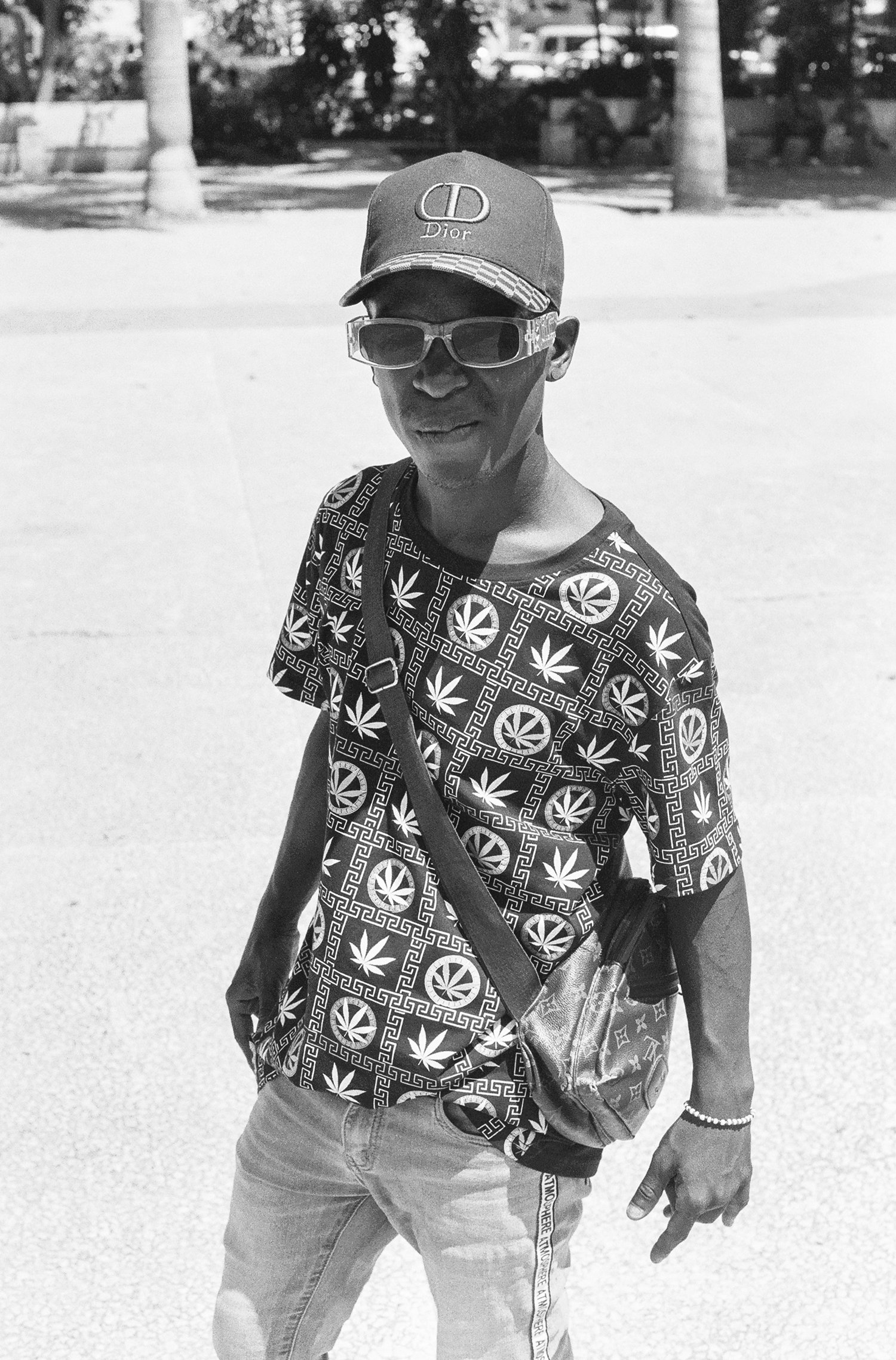

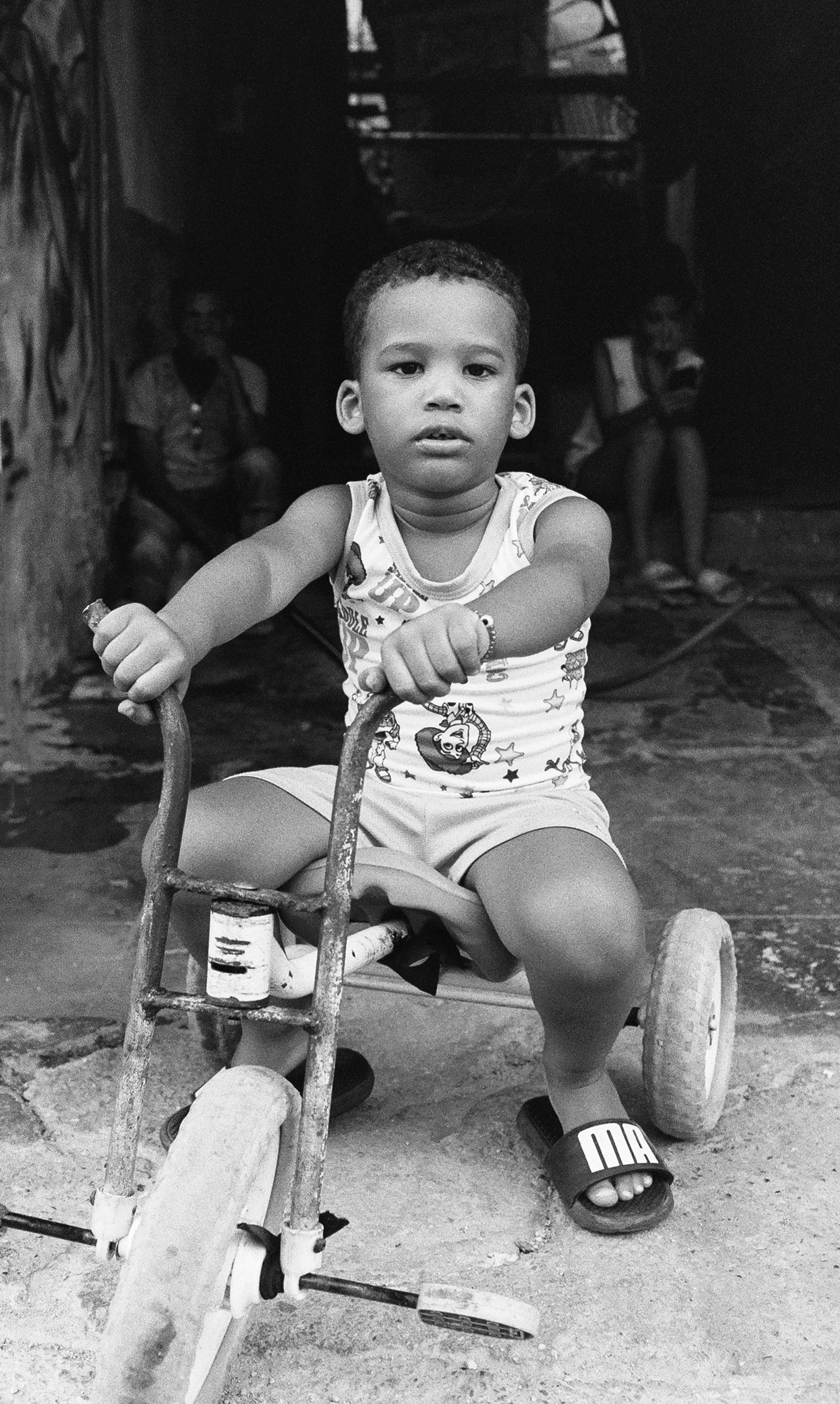

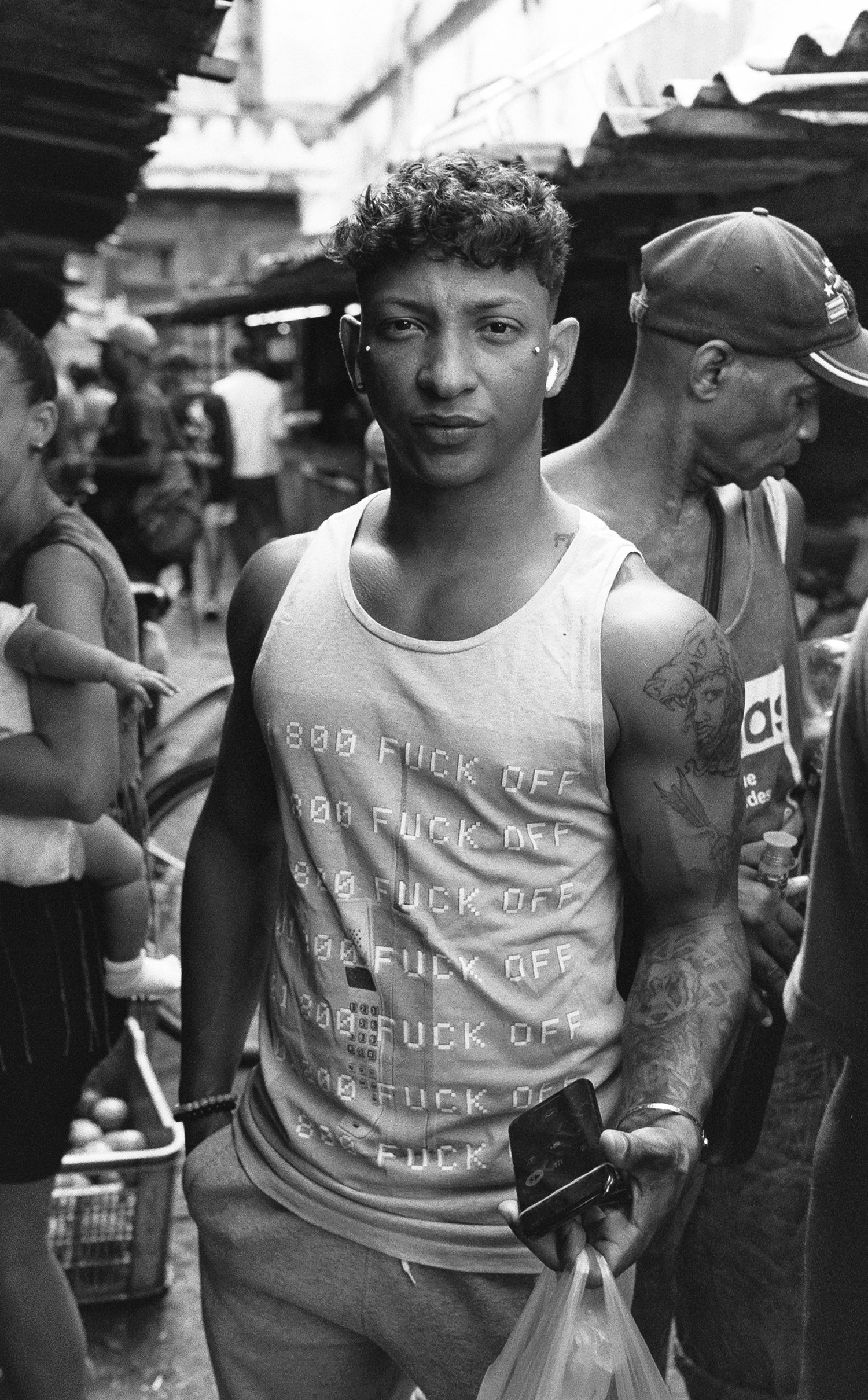

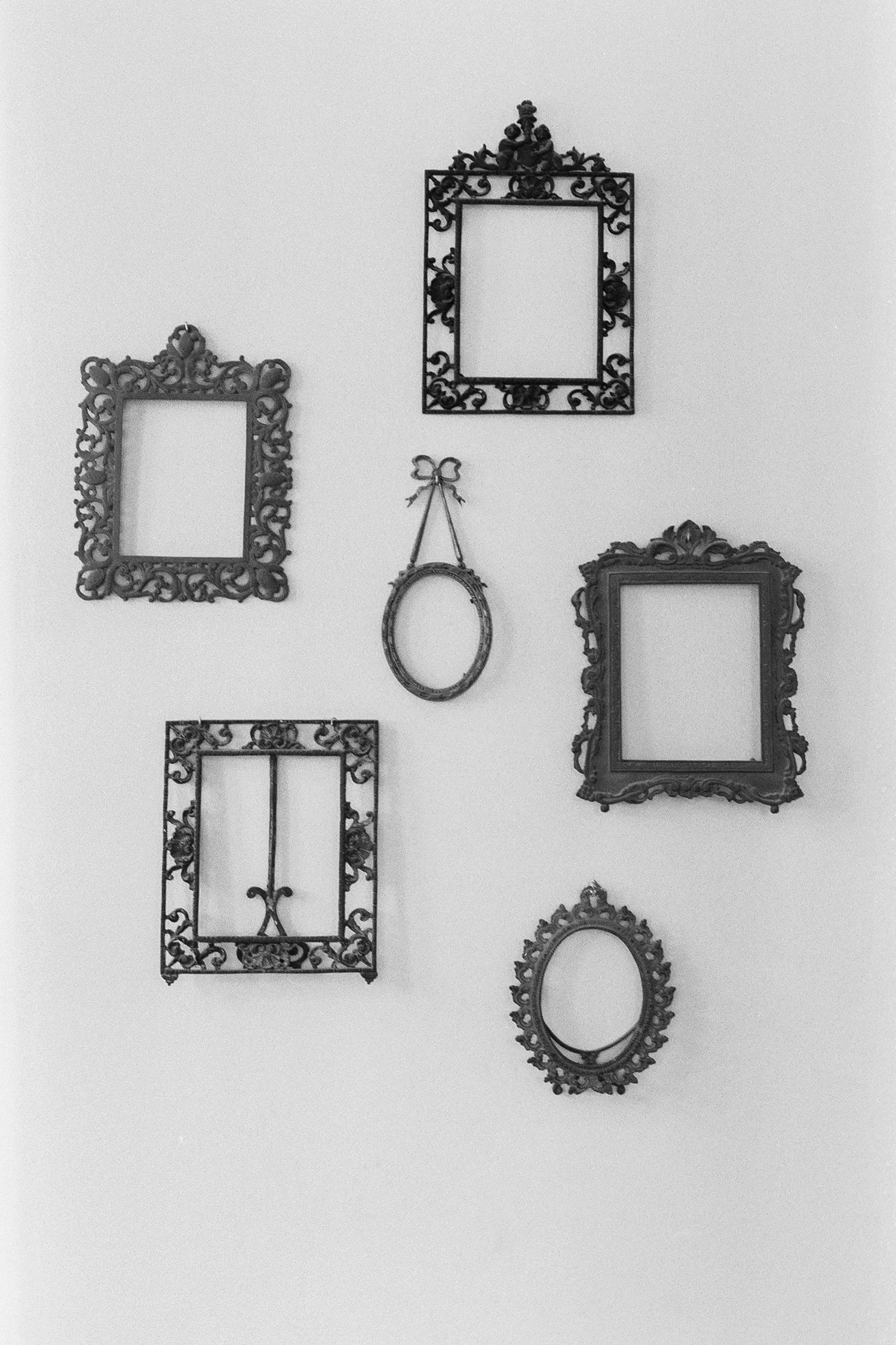

Although fisheries photographers gravitate towards the ocean, we also got in plenty of street photography, capturing portraits of humans of all ages and street animals of all species. We documented antique cars, collapsing buildings, and breathtaking birds. I had the joy of photographing my first ever hummingbird, the Cuban Emerald. And we did not limit our interest in livelihoods to those based on the water. We met and photographed ranchers, farmers, and even a carbonero, or coalman—a man named Daniel who manufactures charcoal by burning giant log piles.

I am surely not the first photographer to quote famous photojournalist, Lewis Hines when he said, “If I could tell the story in words, I wouldn’t need to lug a camera.” Jay’s fitness app told us we walked about ten miles on most days of our trip—ten miles hauling backpacks full of metal and glass. A pencil and paper would have been lighter to travel with, but the story of Cuba is truly a visual one. The scenes are hard to do justice with words. Anachronistic architecture pairs strangely next to teens with facial piercings roller blading in the streets; brightly colored flowers and vegetation alien to the Northeast U.S. adorn city walls; character is written on the faces of our subjects as well as on the peeling walls behind them—all things you must see to truly understand.

Jay Fleming photographing a workboat at the working waterfront in Cojímar, Cuba.